I have been a student for most of my life. Along the way, I've encountered a great variety of teaching styles. Many of my own experiences as a student have inspired the way I think about teaching; my time on the teaching team for an undergraduate class has made these ideas more concrete. I've been lucky to learn from some great teachers, and I am shaped by the experiences of the students I've met. My teaching philosophy can be summarized by the following points:

- Clarity in designing lectures and assignments. Introducing students to the foundational concepts of mechanics is something I take seriously.

In my teaching, I try to introduce advanced topics clearly and systematically, with a heavy emphasis on the scaffolding of concepts.

For example, students should develop a strong command over concepts related to deformation kinematics before constitutive laws are introduced.

In my experience, effective scaffolding requires ample opportunities for students to receive feedback on their learning (more thoughts on this below).

To build understanding and confidence, I like to provide worked examples with plenty of explanations, followed by a variety of exercises: some of which are similar to worked examples but others which go beyond extensions. (Students tend to be really good

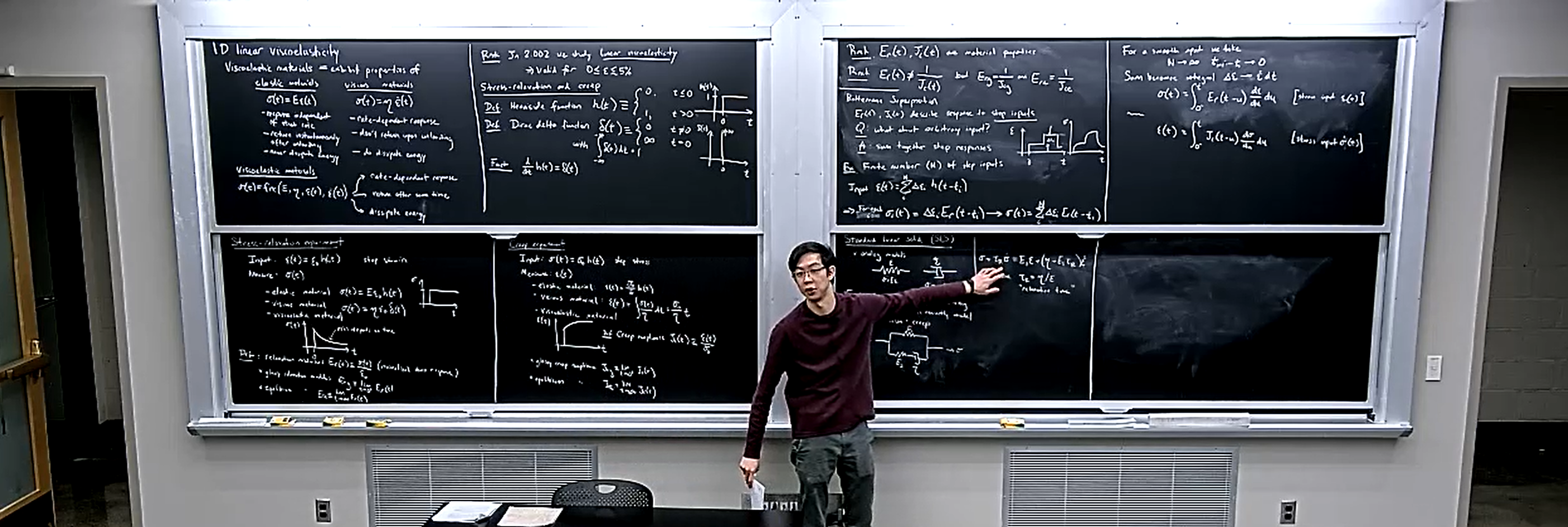

at pattern-matching... sometimes a little too good.) You can see an example of this style in my notes.

More broadly, each lecture and assignment should be constructed around clearly stated learning objectives. Just as we design experiments to measure material properties, we should design lessons and assignments to assess students' understanding of these concrete objectives and to reinforce areas of weakness. Although mechanics is a field dominated by assessments of the "worked problem" type (e.g., "find the stress field given the deformation"), a key tool for assessing understanding is the use of open-ended concept questions. Asking students to explain a concept in their own words is a straightforward method of evaluating how they build and connect ideas in their minds. - Enthusiasm. You've probably sat through a lecture while the instructor either (i) reads text directly off of a presentation at the

rate of a million slides per minute, or (ii) stands with their back to the room, copying notes onto the chalkboard, maybe saying a few words in a monotone voice. This lack of enthusiasm is passed on to students, who consequently lose interest in the content of the course as soon as they leave the room.

Conversely, one of my favorite teachers could have had a second career in acting. His interaction with the class was vibrant, dynamic, and memorable: he would use the classroom

like a stage, he would change the dynamics and the tempo of his voice during the course of the lecture, and his boardwork consisted of only the essential content, so he wouldn't

succumb to the awkward silence associated with writing long sentences with his back turned.

Now, admittedly, my personality is generally more reserved than that, but I try to embody this enthusiasm in my own teaching. Thinking of each class presentation (lecture, review session, even laboratory session) as a kind of performance helps to keep students engaged. Like playing Chopin, or like a quarterback running an effective two-minute drill, controlling the tempo is everything. When I prepare the appropriate material, I organize it to be centered around one or more key messages, then I build up to each one, slow down for emphasis, then move on. When I am genuinely excited and enthusiastic about the content, I have found that the students will match my energy. - Learning by doing. Having worked with 100+ students in upper-division mechanics classes, an overwhelming majority of them self-categorize as "kinesthetic", i.e., they say they learn best by doing. (Have you ever tried to host a discussion session immediately after lunch?) Since core engineering courses are typically structured around passive lectures, I try to build in explicit time for active learning. Laboratory sessions are the easiest way to do this, but often large lectures are still necessary. Active learning in the lecture hall can include simple activities like working with a partner or small group to answer a question or work a problem, or getting students involved in classroom demonstrations. These activities also break up long lecture sessions and help with pacing, as much as they do with retention and reinforcement of material. The best activities and demonstrations are ones that students will remember long after they've finished the course. A popular choice has been introducing a design competition, where students have agency and ownership over the outcome, and get to express their creativity (and their competitive spirit).

- Opportunities for feedback. As a student, few things are more helpful than knowing how you're doing with the material, especially if this feedback comes from a source other than yourself. Providing regular opportunities for feedback throughout the course in various forms has an immense impact on student outcomes, including confidence. I have learned that this is best done in the style of low-stakes, formative assessments: problems done independently then discussed as a group; open-ended design challenges with frequent and incremental checkpoints; thoughtfully assembling problem sets to cover the basis of learning objectives. I also intentionally design opportunities to demonstrate improvement over time, even in summative assessments, e.g. writing similar problems on the first midterm exam and the final exam. Finally, a fair grading scheme eases anxiety, allowing students to focus on learning. (My least favorite college course, which shall remain unnamed, had 50% of the course grade depend on the final exam.)

Students sometimes ask me, "if you could teach any course, what would it be?" Here, you can browse a syllabus I wrote for a fictitious course Mechanics of Architected Materials that I would like to teach in the future.